Derandomisation and Randomised Rounding

Derandomisation

-

Sometimes it is possible to “derandomise” a randomised algorithm Arand and obtain a deterministic algorithm Adet.

-

The performance of Adet is the same as the expected performance of Arand.

-

When successful, we can use randomisation at no extra cost!

(except a polynomial running time overhead).

-

Different methods for derandomisation.

-

Algorithm: For each variable xi, set xi to 1 with probability 1/2 and to 0 with probability 1/2.

-

Algorithm: Set variable xi to 1 or 0 deterministically, and the remaining variables to 1 with probability 1/2 and to 0 with probability 1/2, as before.

-

To maximise the expected value W of the algorithm.

-

If 𝑊 is the number of clauses satisfied then we have:

𝔼[𝑊] = 𝔼[𝑊|𝑥 ←1]⋅Pr[𝑥 ←1]+𝔼[𝑊|𝑥 ←0]⋅Pr[𝑥 ←0]

= 1/2 (𝔼[𝑊|𝑥 ←1] * +𝔼[𝑊|𝑥 ←0])

-

We set x1 to 1 if 𝔼[𝑊|𝑥1 ← 1] ≥ 𝔼[𝑊|𝑥1 ← 0] and to 0 otherwise.

-

Generally, if b1 is picked to maximise the conditional expectation, it holds that: 𝔼[𝑊|𝑥 ←𝑏 ]≥𝔼[𝑊]

Applying this to all variables

-

Assume that we have set variables x1, …, xi to b1, … bi this way.

-

We set xi+1 to 1 if this holds and to 0 otherwise.

𝔼[𝑊|𝑥1 ← 𝑏1,𝑥2 ← 𝑏2,…,𝑥i ← 𝑏i,𝑥i+1 ← 1]≥ 𝔼[𝑊|𝑥1 ← 𝑏1,𝑥2 ← 𝑏2,…,𝑥i ← 𝑏i, 𝑥i+1 ← 0]

-

Again, if bi+1 is picked to maximise the conditional expectation, it holds that:

𝔼[𝑊|𝑥1 ← 𝑏1,𝑥2 ← 𝑏2,…,𝑥i ← 𝑏i,𝑥i+1 ← 𝑏i+1] ≥ 𝔼[𝑊]

In the end

-

In the end we have set all variables deterministically (去随机化).

-

We have 𝔼[𝑊|𝑥1 ← 𝑏1,𝑥2 ← 𝑏2,…,𝑥i ← 𝑏i,𝑥i+1 ← 𝑏i+1] ≥ 𝔼[𝑊]

-

We know that E[W] ≥ 1/2 * OPT

-

We have devised a deterministic 2-approximation algorithm.

-

Is it polynomial-time? Yes

Computing the expectations

- We have to be able to compute the conditional expectations in polynomial time.

𝔼[𝑊|𝑥1 ← 𝑏1 ,…,𝑥i ←𝑏i]= ∑𝔼[𝑌|𝑥1 ←𝑏1 ,…,𝑥i ←𝑏i]

= ∑ i=1^m Pr[clause𝐶issatisfied|𝑥 ←𝑏 ,…,𝑥 ←𝑏]

-

The probability is

-

1 if the variables already set satisfy the clause.

-

1-(1/2)k otherwise, where k is the set of unset variables.

Method of conditional expectations

Recall: Deterministic Rounding

-

For the case of vertex cover we can solve the LP-relaxation in polynomial time, to find an optimal solution.

-

The optimal solution is a “fractional” vertex cover, where variables can take values between 0 and 1.

-

We round the fractional solution to an integer solution.

-

We pick a variable xi and we set it to 1 or 0.

-

If we set everything to 0, it is not a vertex cover.

-

If we set everything to 1, we “pay” too much.

-

We set variable xi to 1 if xi ≥ 1/2 and to 0 otherwise.

Randomised Rounding

-

We formulate the problem as an ILP.

-

We write the LP-relaxation.

-

We solve the LP-relaxation.

-

We round the variables with probabilities that can depend on their values.

-

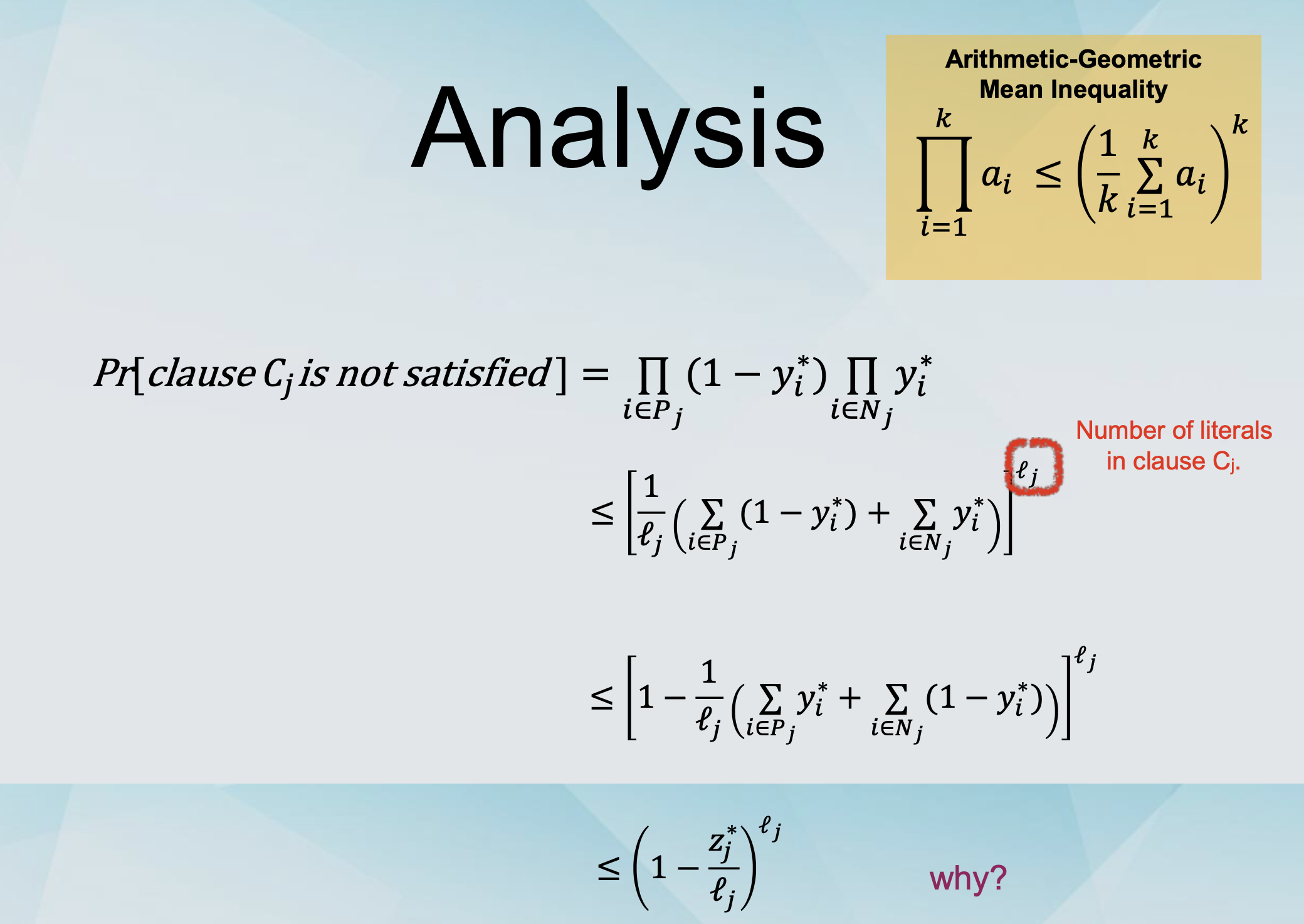

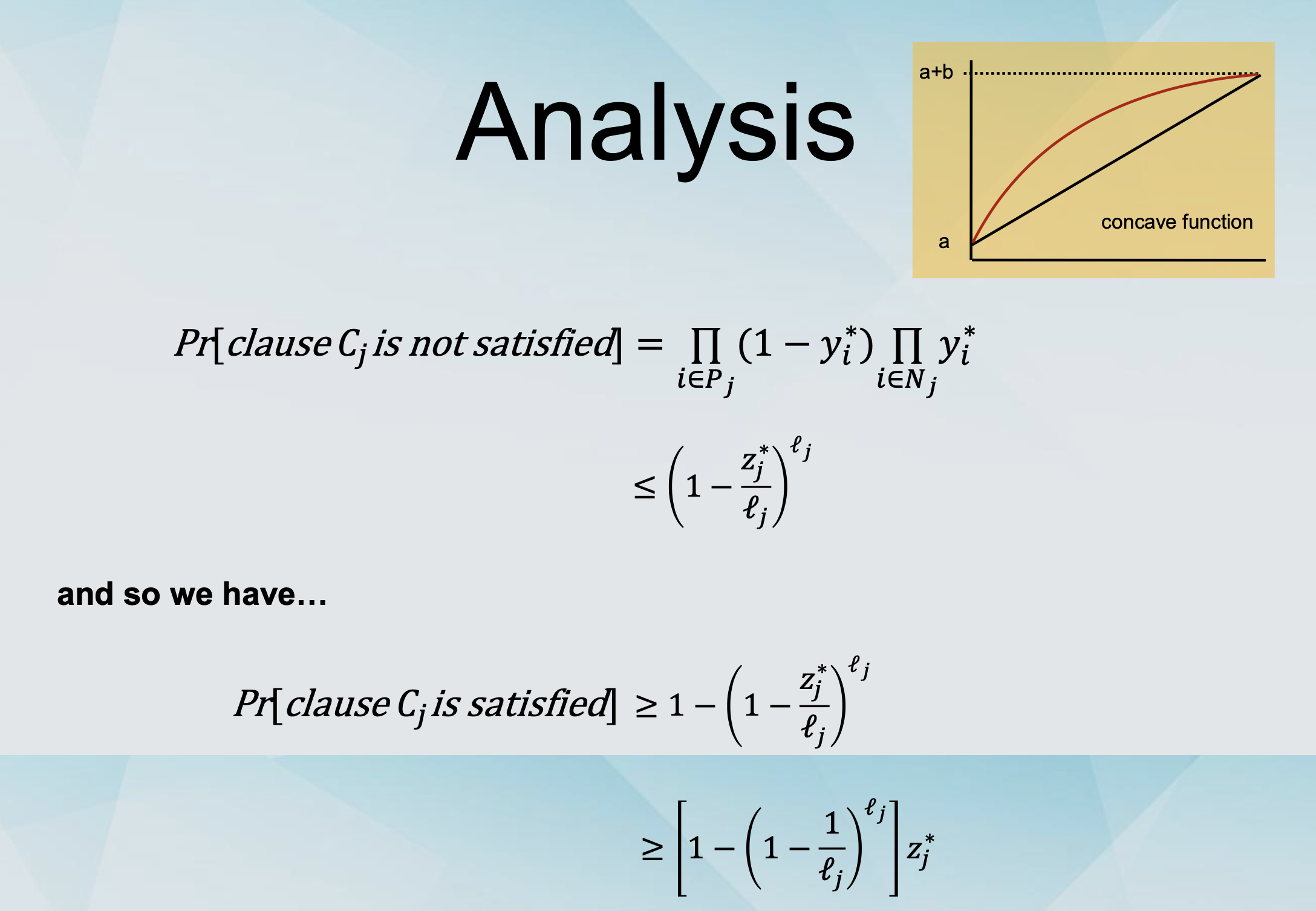

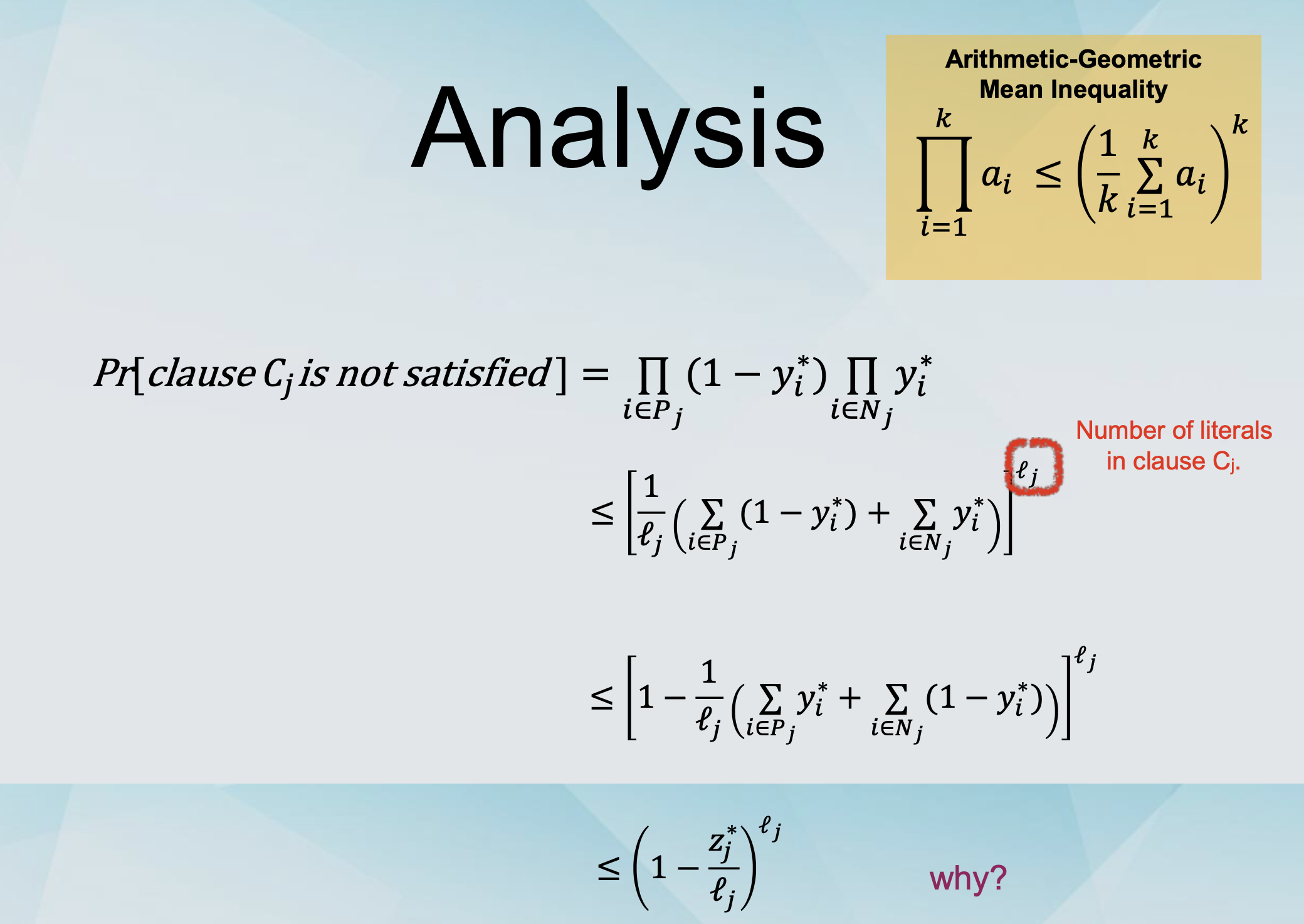

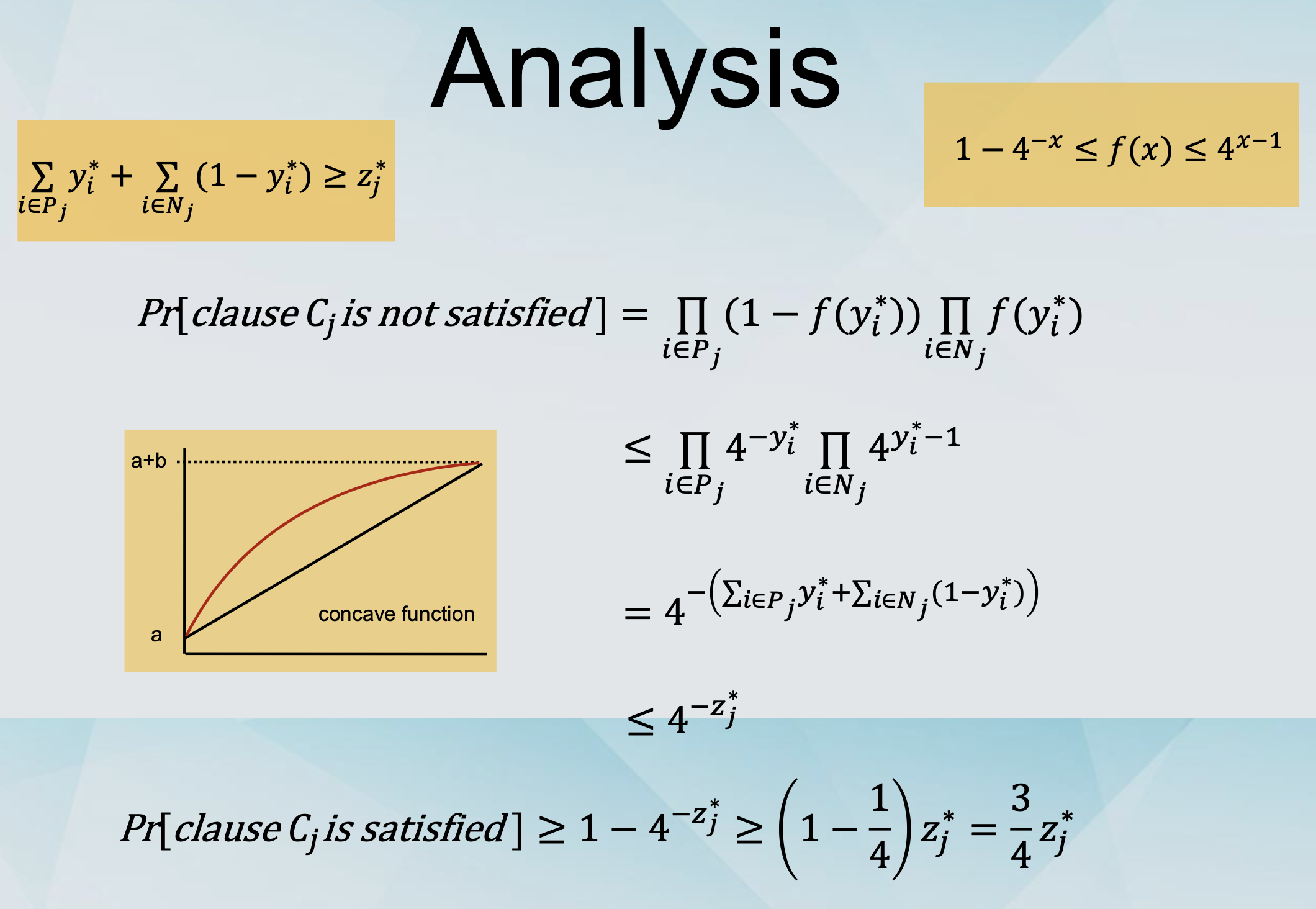

Let (y*, z*) be a solution to the LP-relaxation.

-

Rounding: Set xi to true independently with probability yi*.

- e.g., if y* = (1/3, 1/4, 5/6, 1/2, …) we will set variables x1, x2, x3, x4, … to true with probabilities 1/3, 1/4, 5/6, 1/2, … respectively.

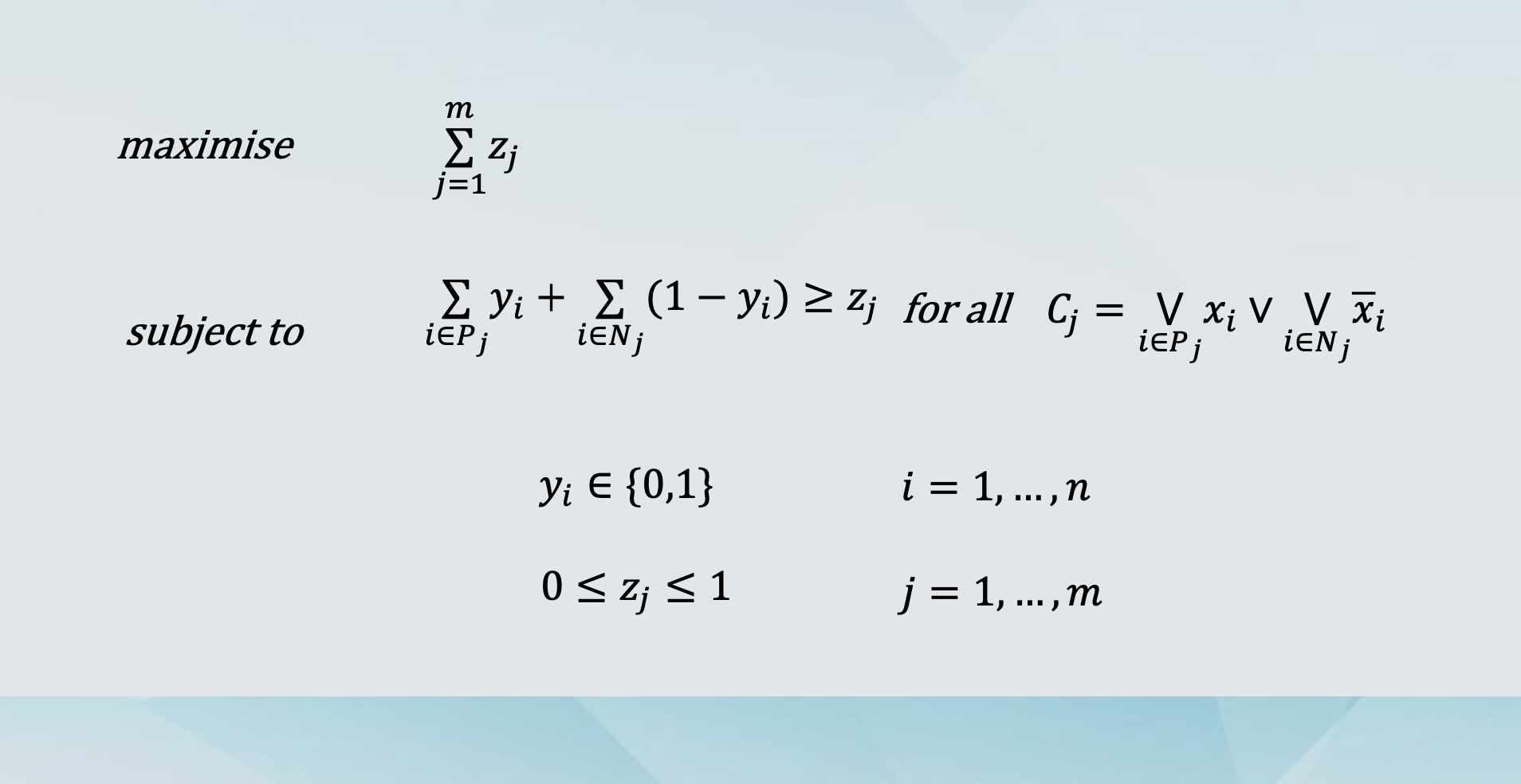

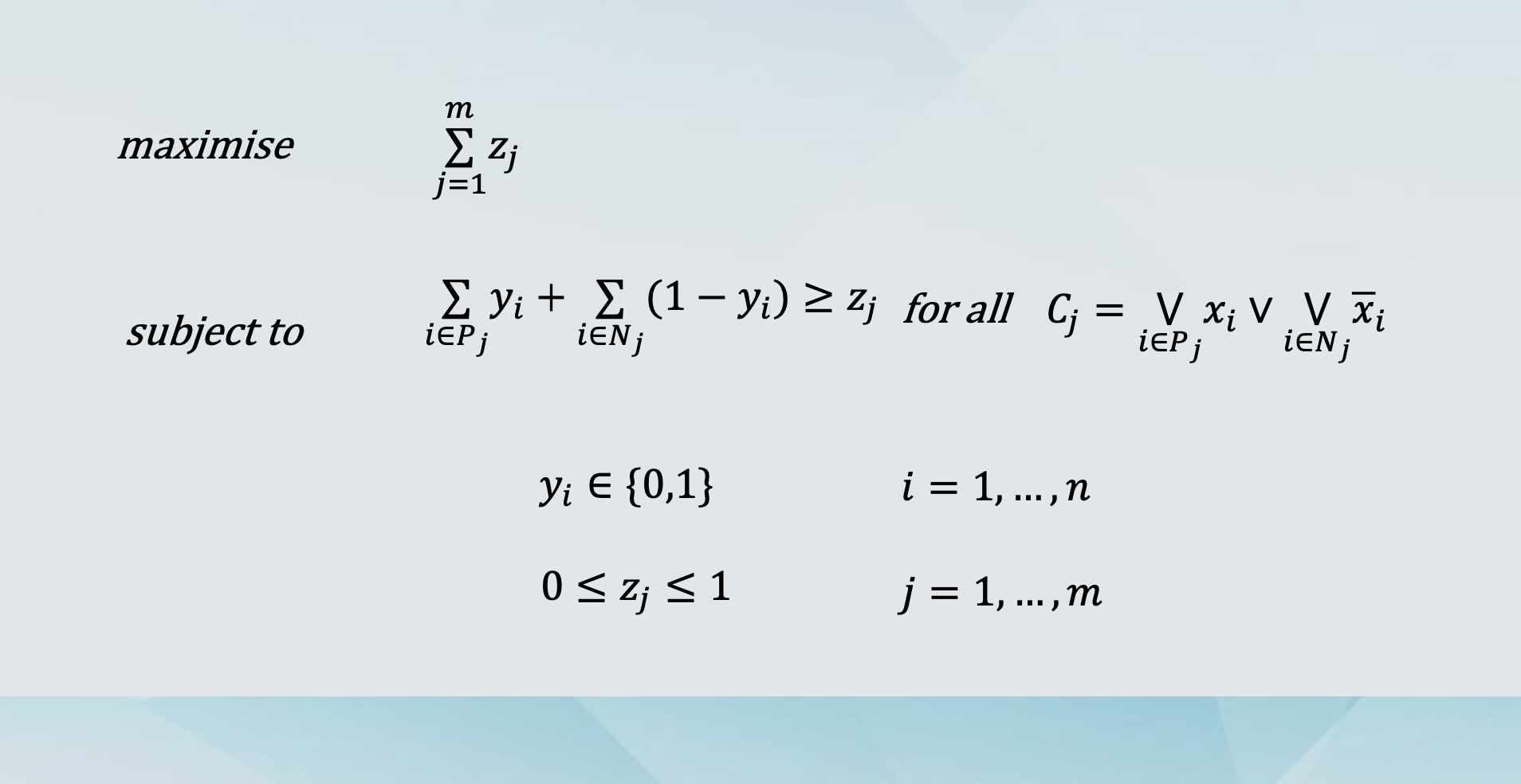

MAX SAT as an ILP

Variables: yi = 1 if xi is true and 0 otherwise.

We denote clause Cj by ⋁ 𝑥𝑖 ∨ ⋁ 𝑥𝑖 𝑖∈𝑃𝑗 𝑖∈𝑁𝑗

Variables: zj = 1 if clause Cj is satisfied and 0 otherwise.

We have the inequality: ∑ 𝑦i + ∑ (1 − 𝑦i ) ≥ 𝑧j

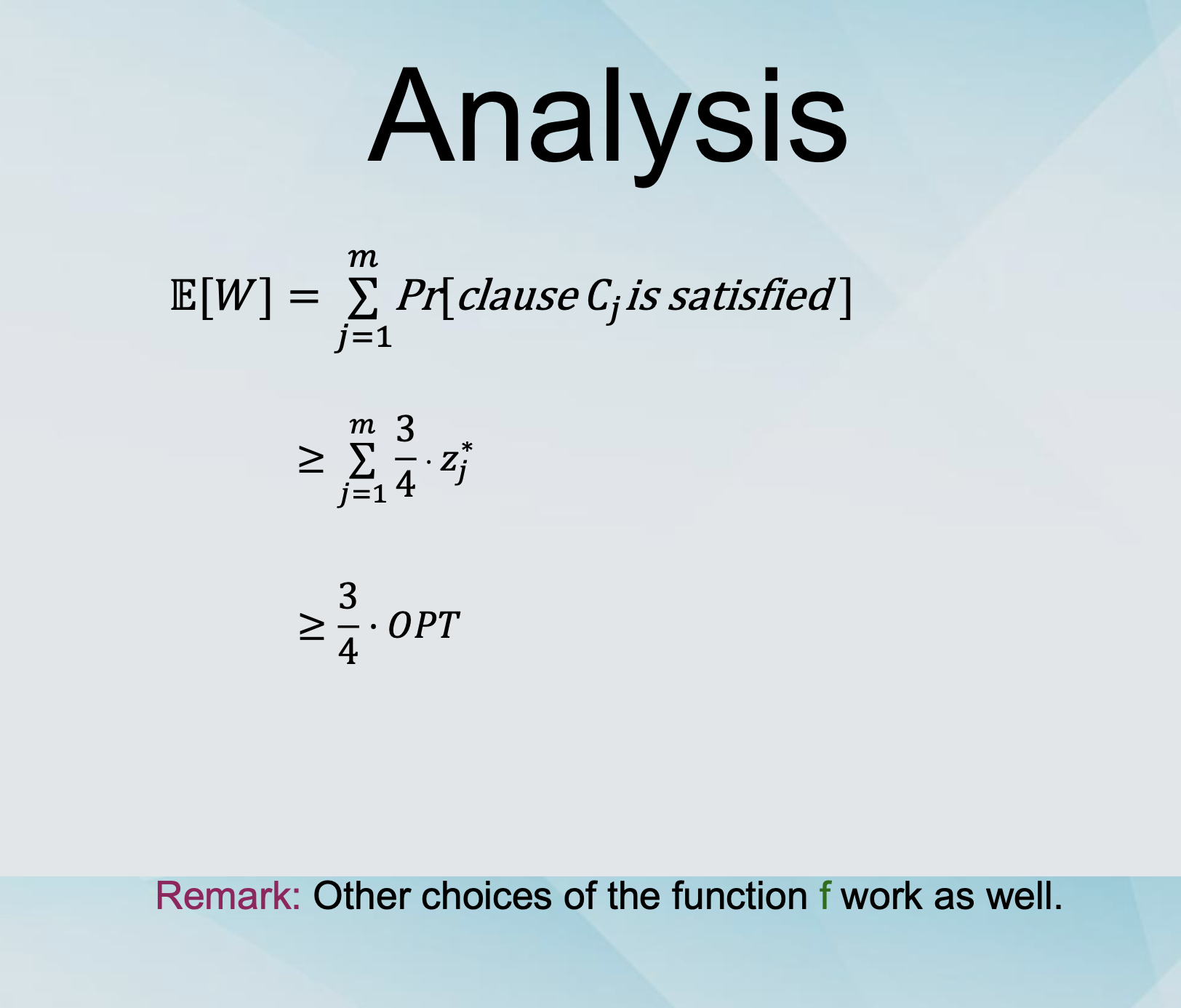

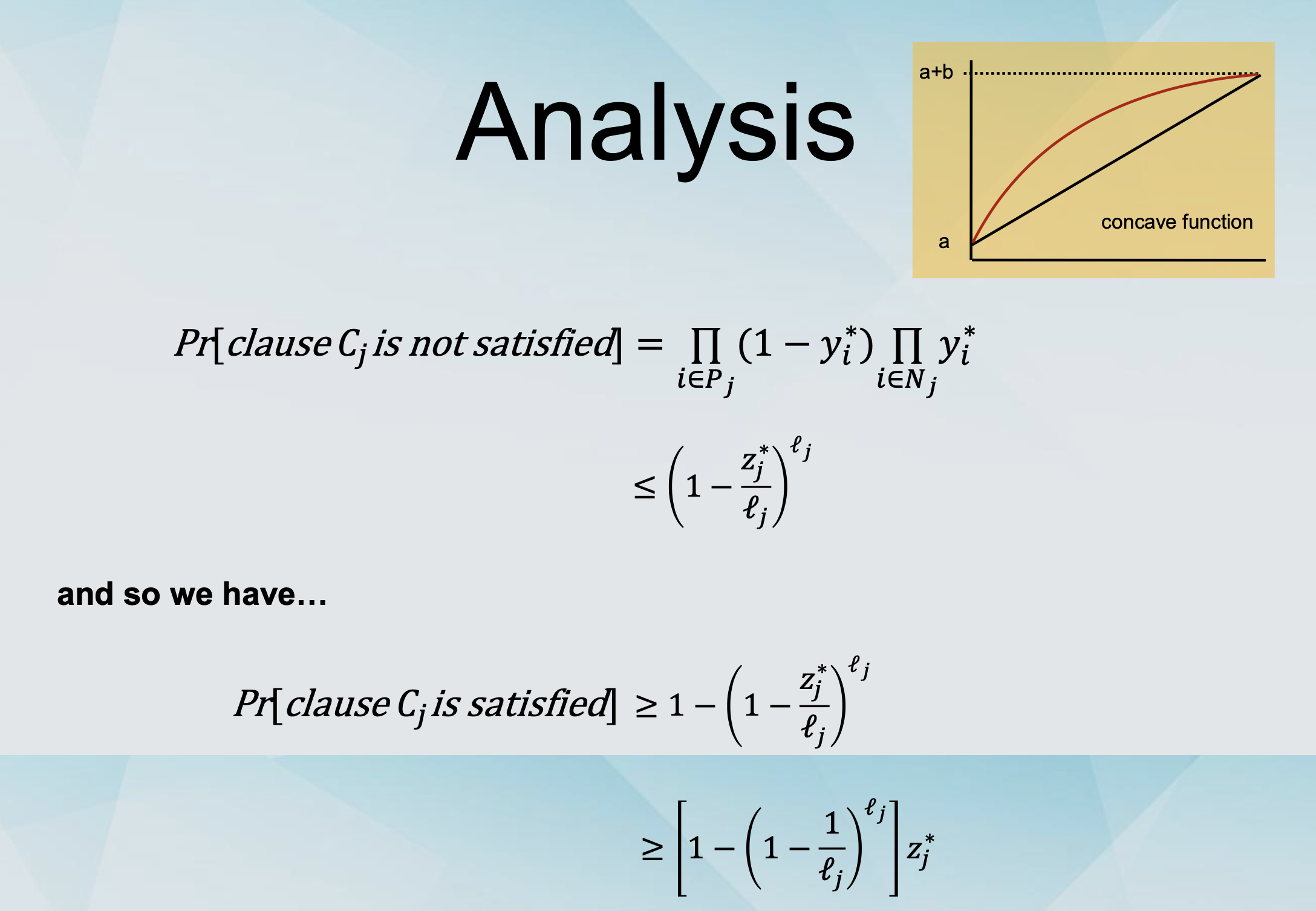

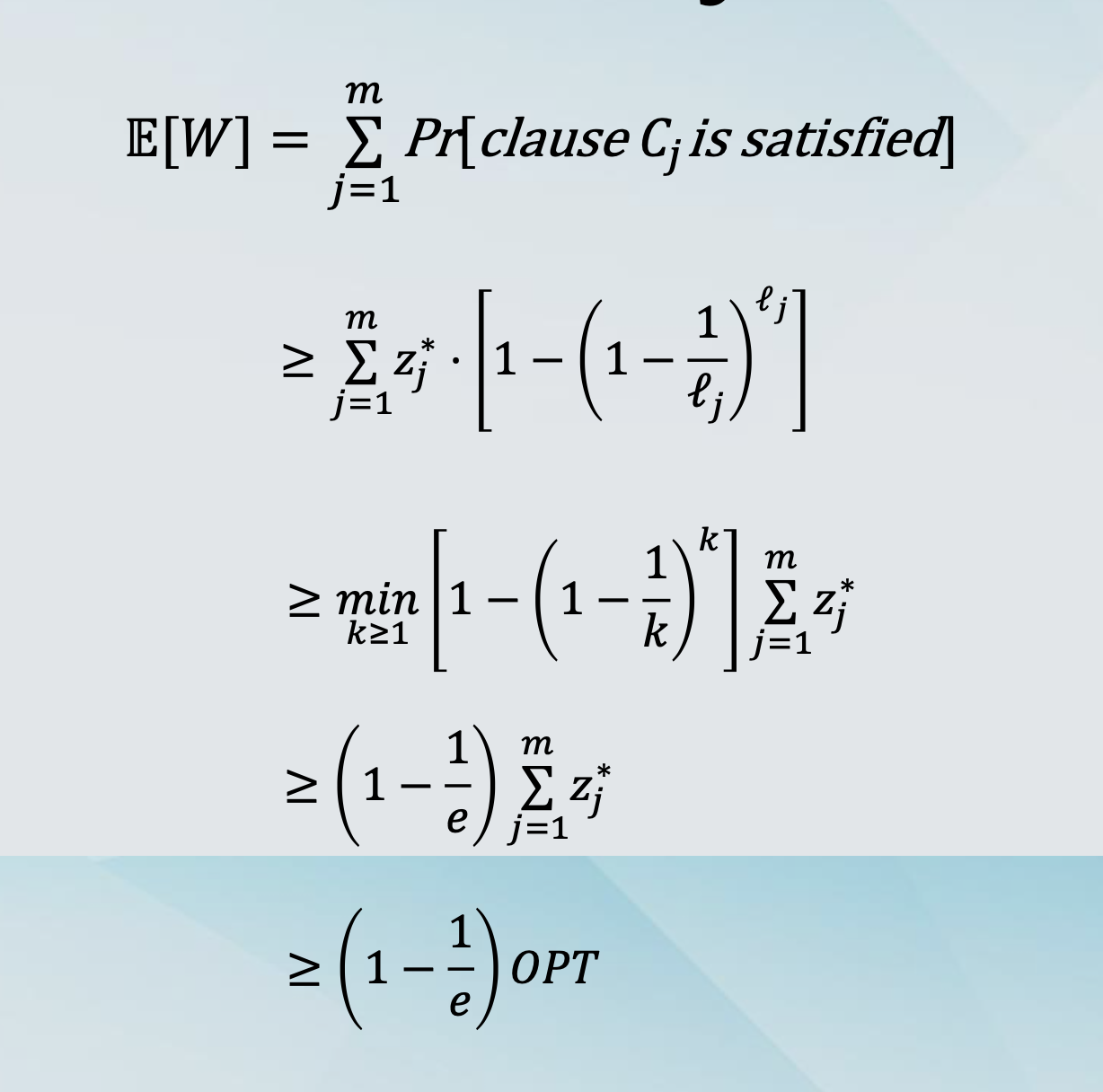

Randomised Rounding for MAX-SAT

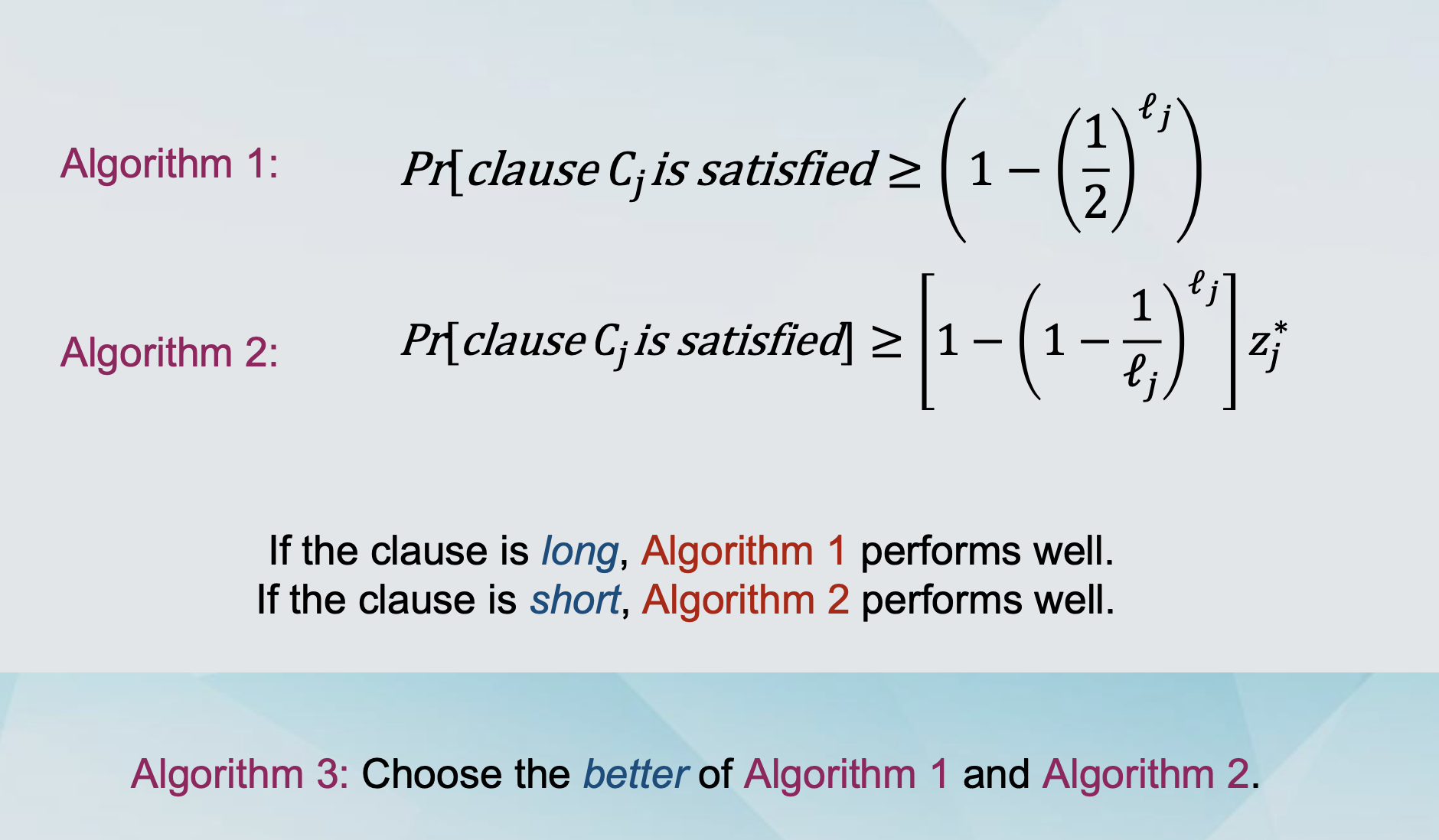

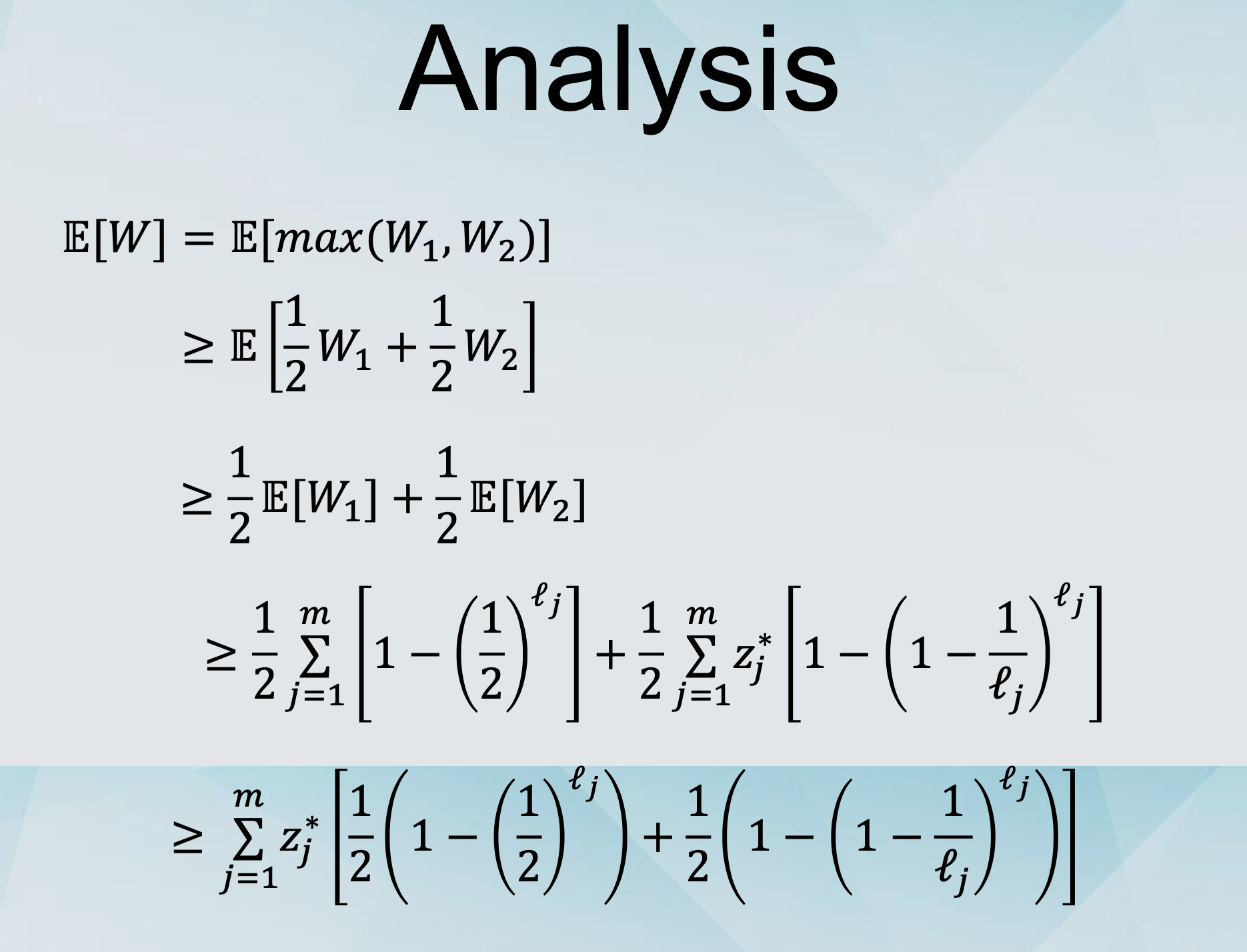

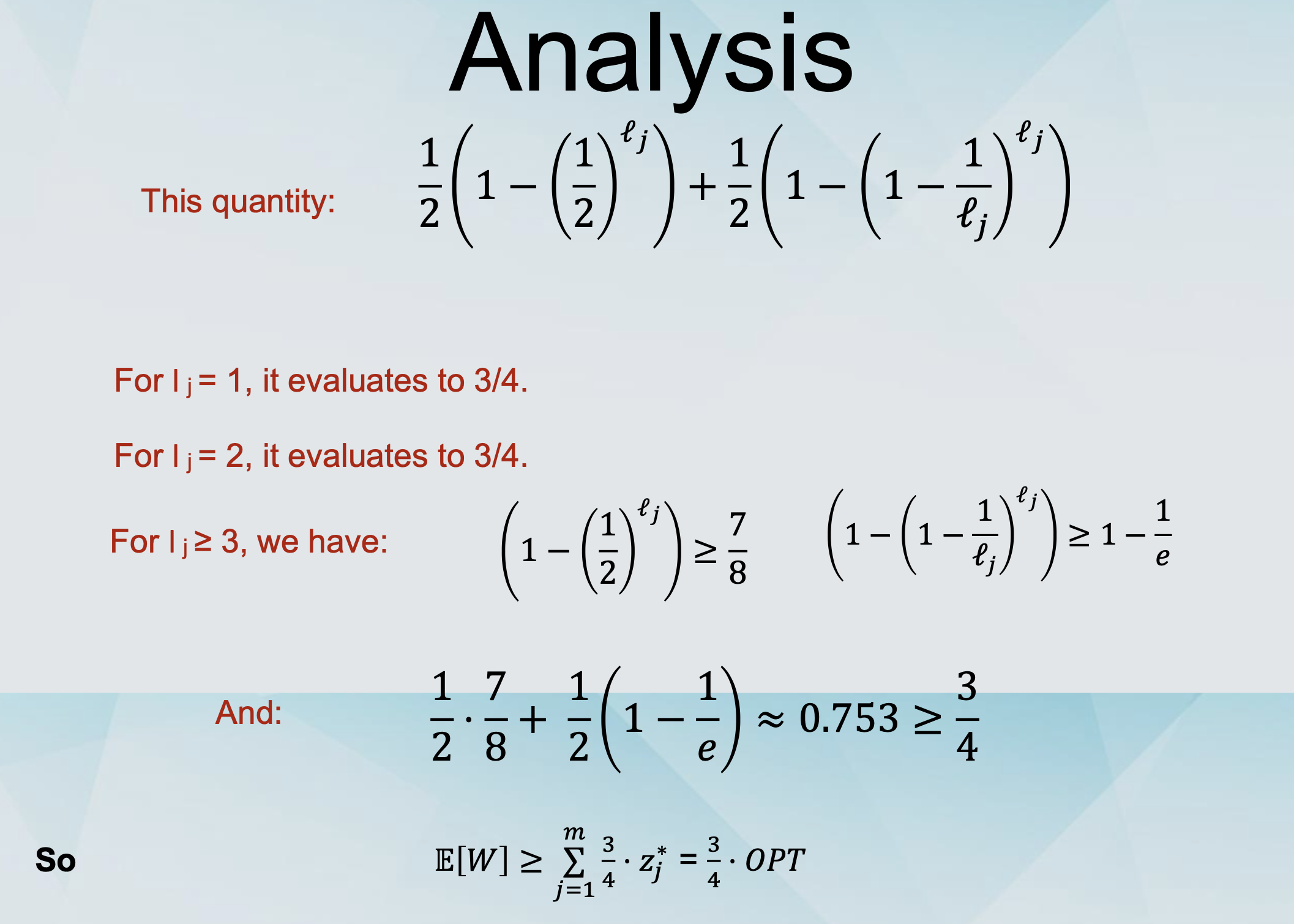

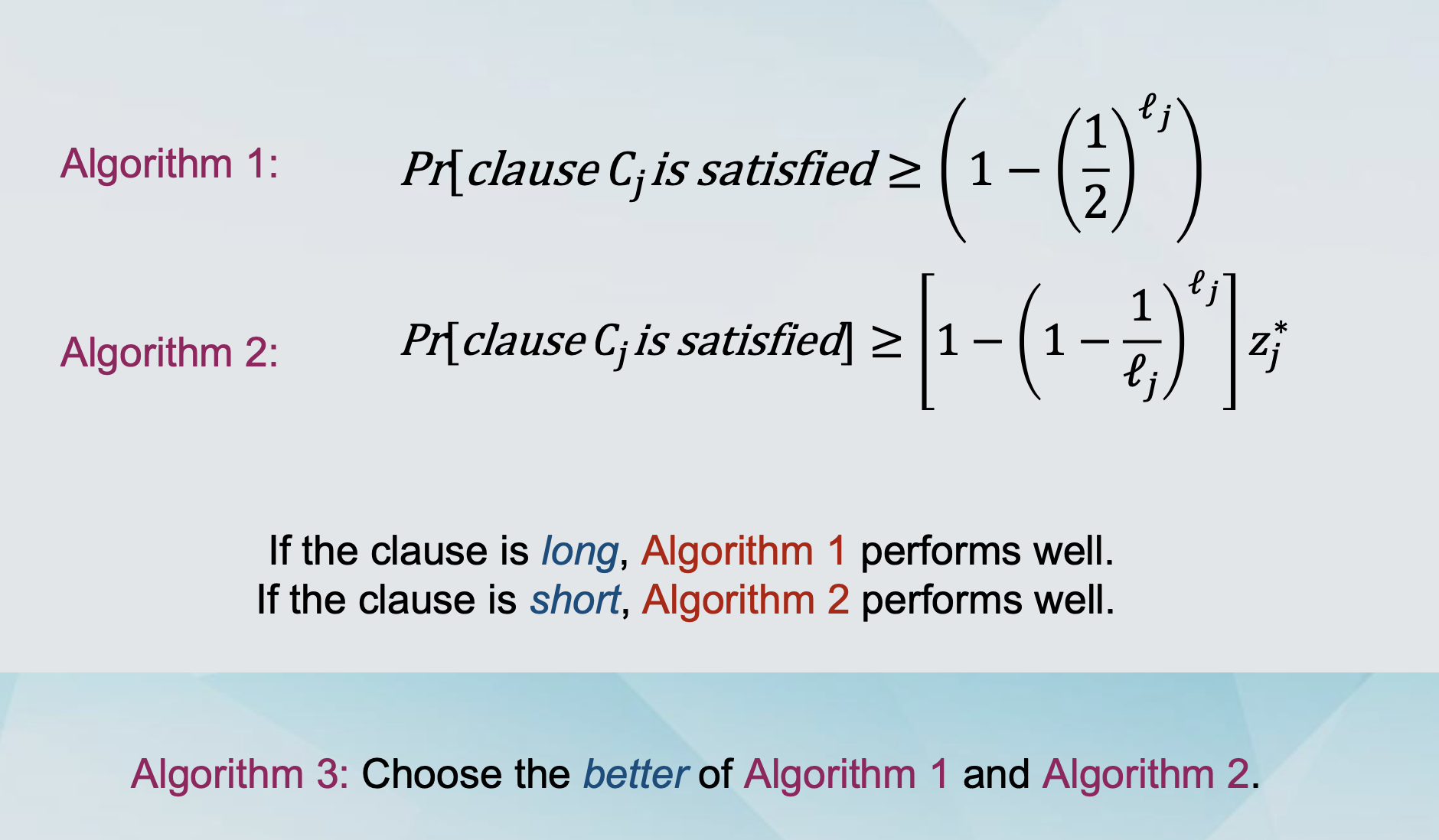

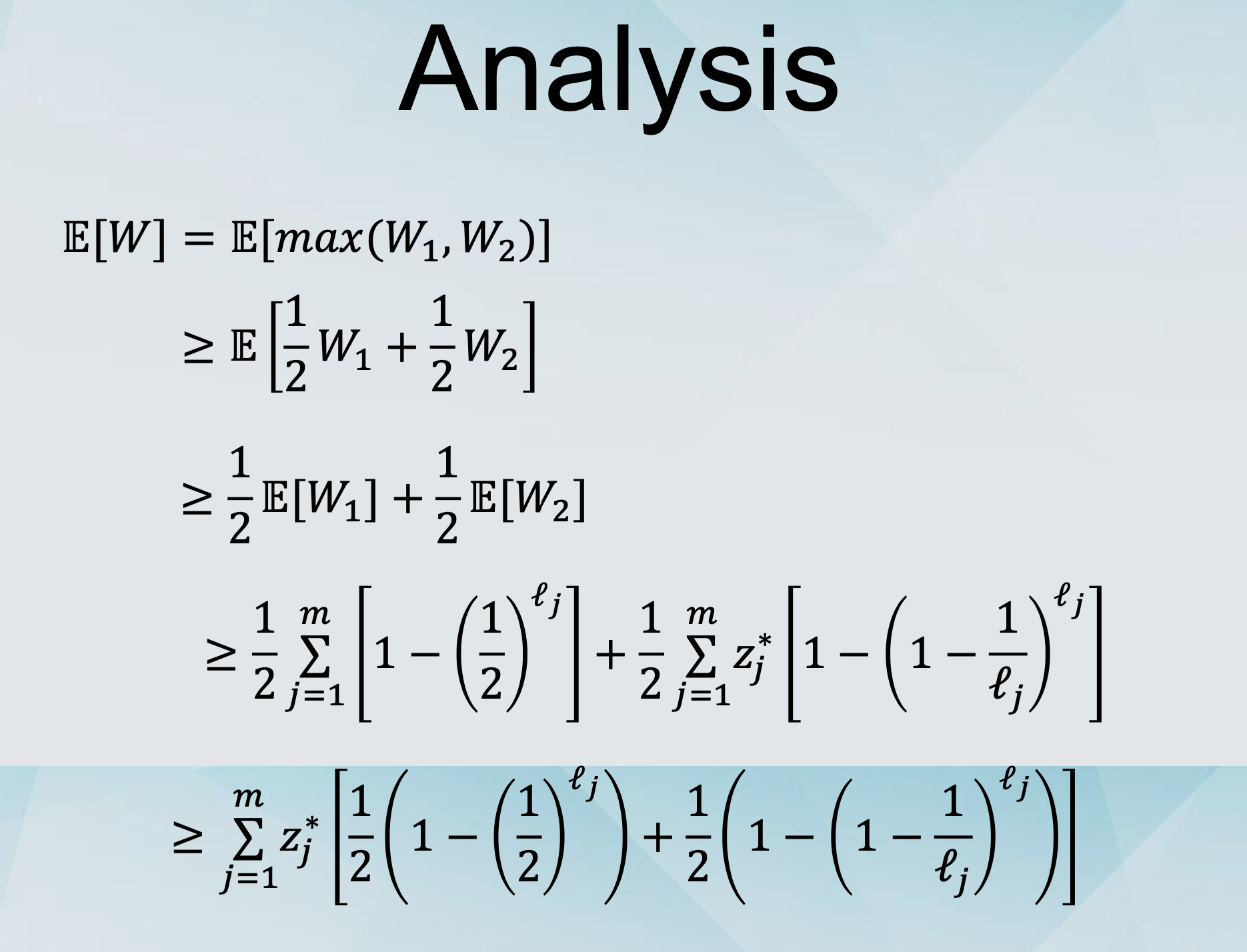

The better of the two

Algorithms for MAX-SAT

-

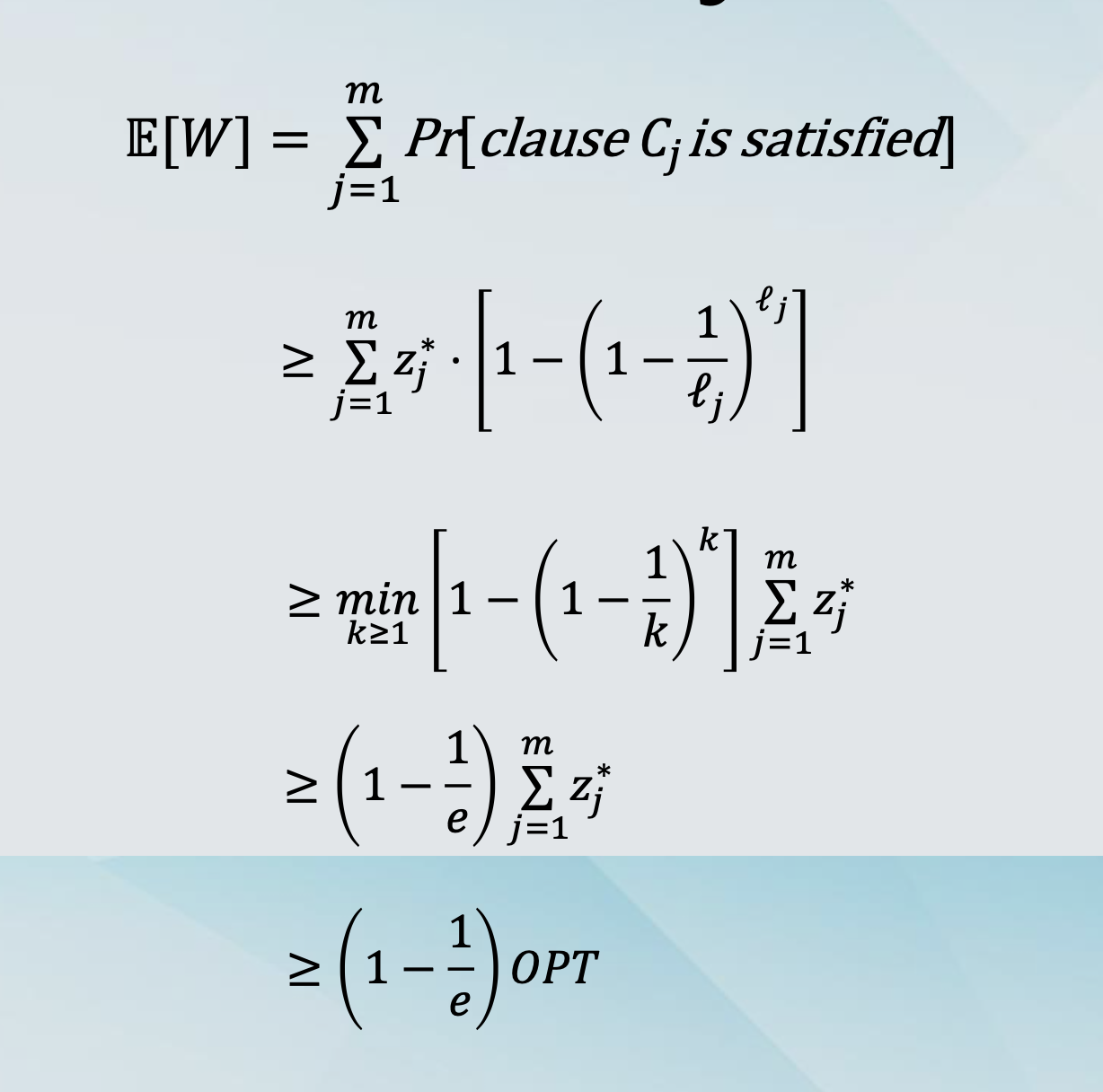

Our Randomised Rounding algorithm gives an approximation ratio of 1/(1-1/e) ≈ 1.59.

-

This is better than 2. (unbiased coin flip for each variable)

-

This is better than 1.618. (why this?)

-

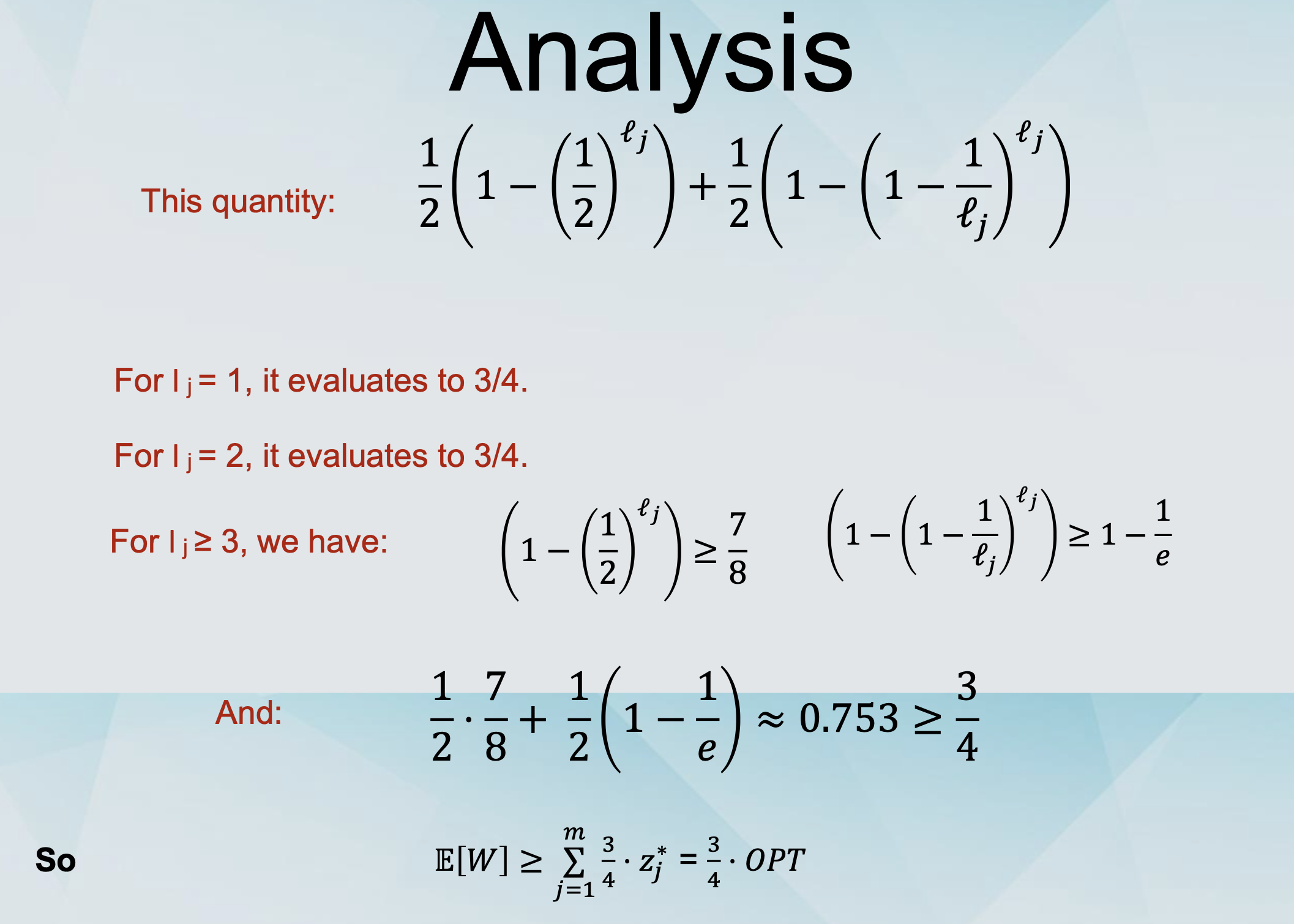

The “better of the two” algorithm has approximation ratio 4/3 ≈ 1.33.

Back to Randomised Rounding

Integrality Gap of MAX-SAT

-

Consider the formula: (x1 ⌵x2)⌃(┐x1 ⌵x2)⌃(x1 ⌵┐x2)⌃(┐x1 ⌵┐x2)

-

The optimal integral solution satisfied 3 clauses.

-

The optimal fractional solution sets

y1= y2 = 1/2 and zj = 1 for all j and satisfies 4 clauses.

-

The integrality gap is at least 4/3.

What does this mean?

-

We can not hope to design an LP-relaxation and rounding-based algorithm (for this ILP formulation) that outperforms our “better of the two” algorithm.

-

Can we design one that matches the 4/3 approximation ratio?

-

Yes we can!

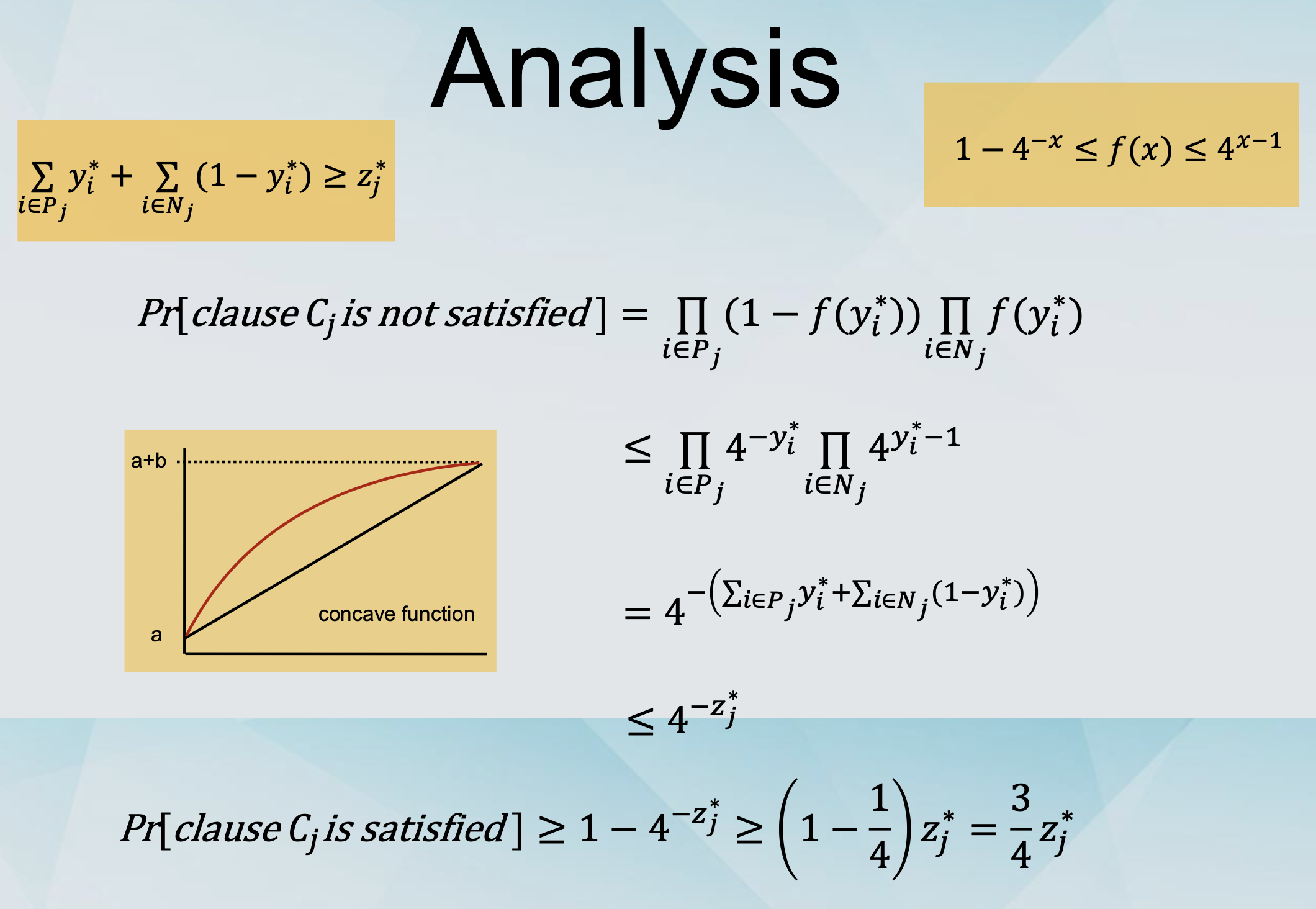

-

Instead of “Set xi to true independently with probability yi*”,

-

We use “Set xi to true independently with probability f(yi*), for some function f.

-

Which function f?

- Any function such that 1 - 4-x ≤ f(x) ≤ 4x-1

Algorithms for MAX-SAT

-

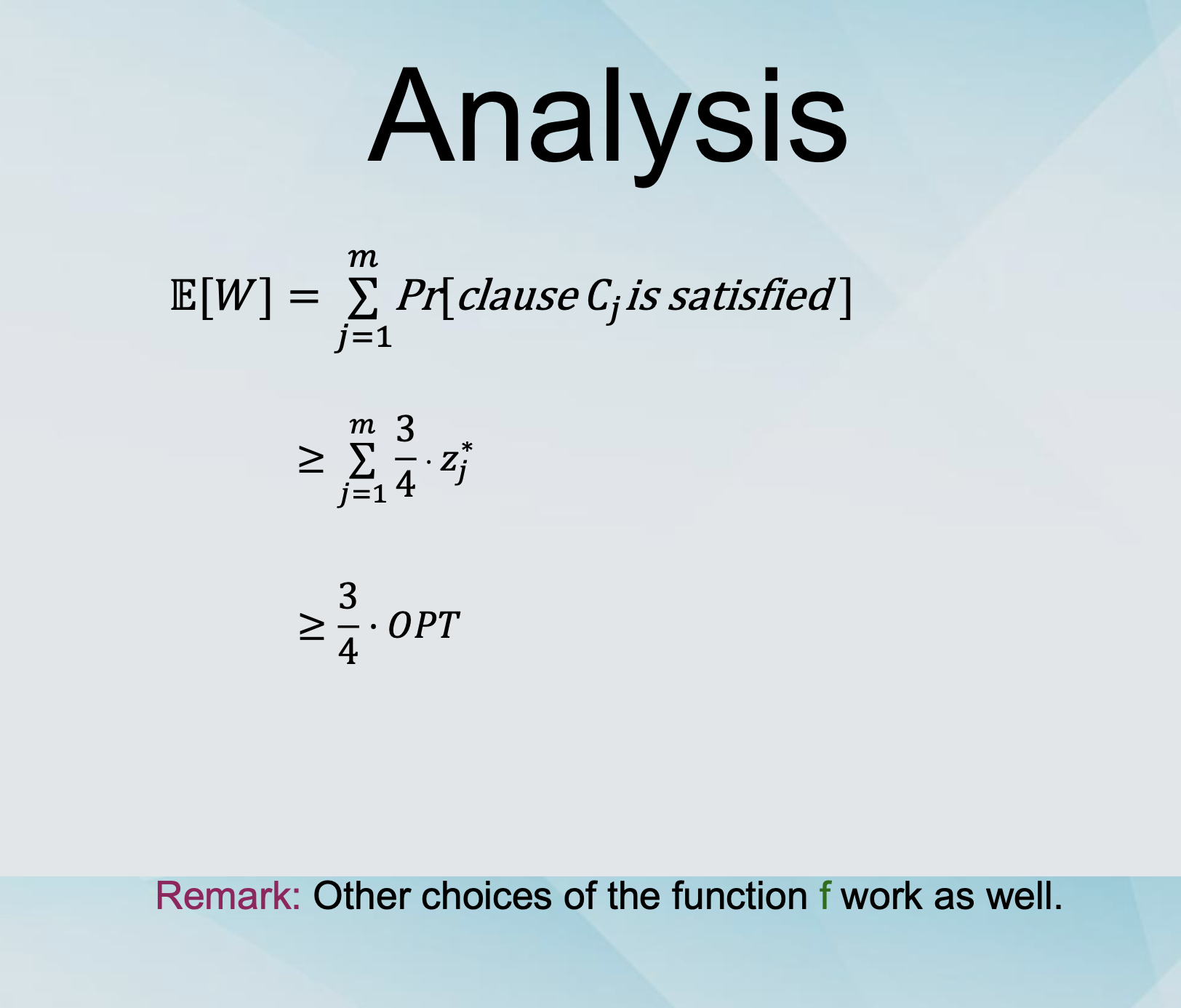

Our first RR algorithm gives an approximation ratio of 1/(1-1/e) ≈ 1.59.

-

This is better than 2. (fair coin flip for all variables)

-

This is better than 1.618. (optimal coin flip for all variables)

-

The “better of the two” algorithm has approximation ratio 4/3 ≈ 1.33.

-

The more sophisticated RR algorithm has an approximation ratio of 4/3 ≈ 1.33.